Tactical Fundamentals

So I want to start writing more about tactics, because we have to lay some groundwork in tactical fundamentals before we can really talk in an informed matter about certain other topics of interest to the Citizen-Warrior. So what exactly do I mean when I say tactics? I think that word gets thrown around a lot these days, so let’s start off by defining what I’m talking about. I like the following definition of tactics from the Merriam-Webster dictionary a lot:

Tactics (N): The art or skill of employing available means to accomplish an end.

Notice that the definition above doesn’t specifically refer to guns or gunfighting. You can employ tactics in any given area of your life when you’re trying to accomplish some kind of goal. When it comes to guns and gunfighting, I believe that a lot of people think of “tactics” or “tactical” as having to do with black rifles, body armor, and Multicam. While we may sometimes discuss tactics in a context that conjures up those images, the reality is that many tactical fundamentals carry over between the military/paramilitary small unit tactics world and the Citizen-Warrior CCDW world.

Let me give you an example. ATA Associate Instructor Matt Gilson recently wrote an introductory article about Church Security. It’s only an introductory article because we haven’t yet laid the groundwork to be able to get into the nitty-gritty of church security. When we talk about church security, we’re essentially talking about defending a fixed location, right? So wouldn’t it make sense to first learn about the principles of defense (SAFESOC) first? What about the procedure for analyzing a problem situation (METT-T)?

Here at ATA, we want to enable you to be able to handle your own security. If we just start making generic recommendations about what to do, without first laying the background for why you need to do it, then we’re only giving you half the information. Our hypothetical examples wouldn’t necessarily apply in your particular situation. On the other hand, if we give you the tools you need to think tactically, then you should be able to apply the lessons learned to your unique situation to good effect.

With that foundation established, let’s move on to today’s topic: The Supported/Supporting relationship.

Supported and Supporting

This is probably the most basic of all the tactical fundamentals: Two is more than twice as good as one.

“Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their toil. For if they fall, one will lift up his fellow. But woe to him who is alone when he falls and has not another to lift him up! Again, if two lie together, they keep warm, but how can one keep warm alone? And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him…” -Ecclesiastes 4:9-12

When we refer to the Supported/Supporting relationship (Ted and Ting for short), we are talking about the relationship between two fighters, be they two individuals or two groups. In a military context, we generally designate a maneuver element (also called an assault element) to actually accomplish the assigned mission. We may also refer to this element as the Main Effort. Whatever it is that we are trying to get done – the Main Effort is the person or unit that will make it happen.

The Main Effort can’t accomplish his mission alone, however. He needs backup, he needs support. So that’s why we will also designate a support element as his Supporting Effort. It logically follows that the maneuver element is the unit being supporTED and the support element is the unit doing the supporTING. Therefore, we refer to the maneuver element as Ted and the support element as Ting in this context. Ting helps Ted accomplish Ted’s mission.

An Example of the Combined Arms Dilemma

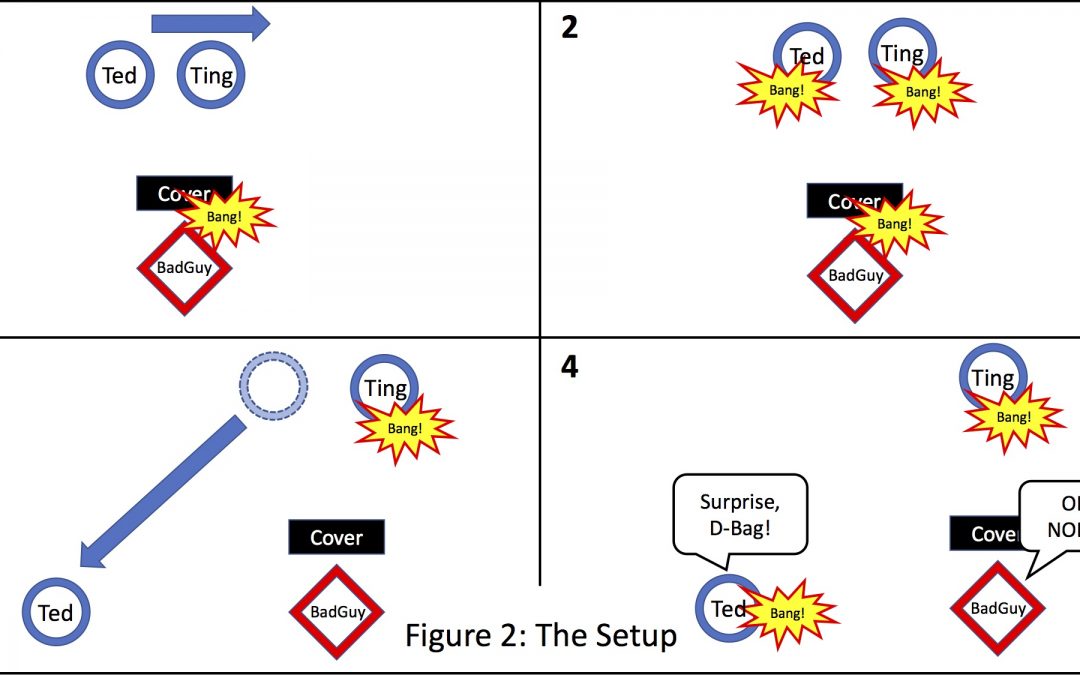

One of the most basic applications of Ted and Ting in the military context is to catch an enemy in a crossfire by using a flanking maneuver. The end state that we are shooting for looks like this:

As you can see, the good guys (blue circles) have the bad guy (red diamond) in a dilemma. Even though the bad guy might be taking cover from the good guy to his front, that means he is vulnerable to the good guy to his left. The good guys didn’t start in this position, but this is where they ended up. They did this through the use of the Supported/Supporting relationship. Let’s go back and see how this occurred.

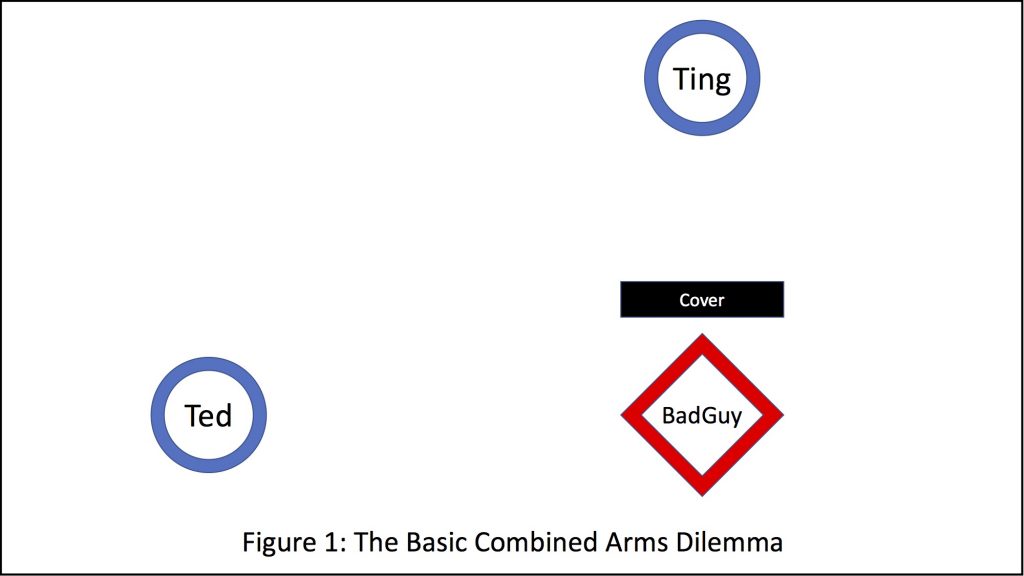

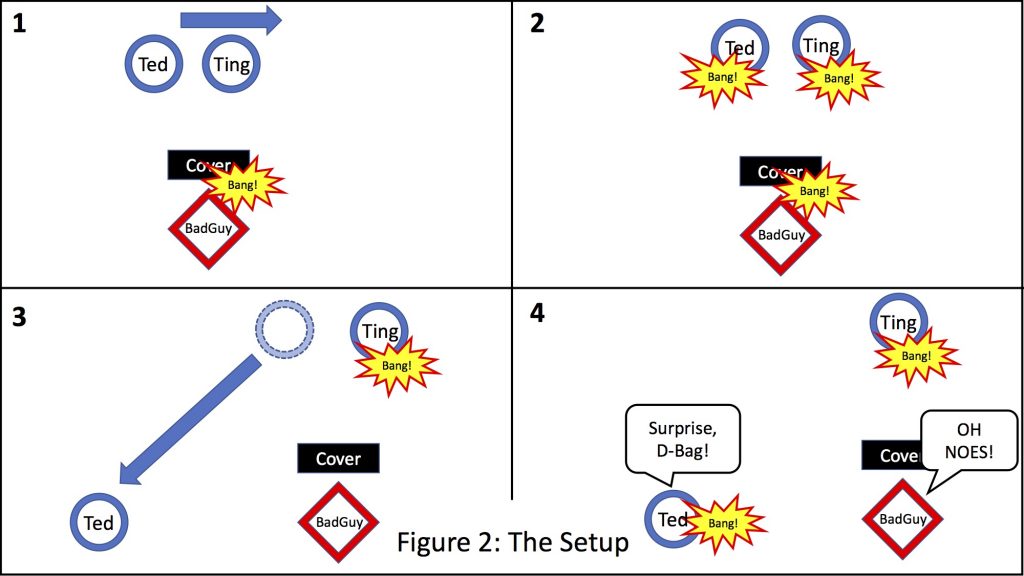

Here is what’s happening in Figure 2: (1) The good guys are moving along, doing the right thing (an Armed Couple out for the night, two fire teams on patrol, it doesn’t matter who they are). While the good guys are moving, the bad guy attacks them from behind a covered position to their flank. Right now, despite it being two vs. one, the bad guy has the upper hand. He is protected by his cover and can fire on both of the good guys without having to change his aim too much from one to the other.

(2) The good guys react by returning fire to keep the bad guy thinking more about getting shot than about shooting the good guys. (3) While this happens, one good guy (Ted) starts to move to the bad guy’s flank. Ted is going to be our maneuver element or Main Effort, because the thing that needs to be accomplished right now is getting into a position where the bad guy doesn’t have good cover from the good guys’ bullets. Ted’s buddy Ting is supporting him by keeping up a constant stream of accurate fire on the bad guy’s position with the intent of keeping the bad guy from smoking Ted while he’s moving around to flank.

(4) Once Ted gets in position, the bad guy is caught in a crossfire, or as we would say in the military context, he is caught in a Combined Arms Dilemma. At this point, no matter which way the bad guy goes, he can’t keep from getting shot. He’s screwed.

Role Reversal

So what if Ted made it around to the bad guy’s flank and he was unable to complete the mission? What if he was wounded or something else changed? Let’s say this is the situation: Our two heroes are patrol officers. They will certainly respond to deadly force with their own deadly force, but at some point, one of them has to approach the bad guy and apprehend him (or his corpse). Ted makes it to the bad guy’s flank, but he gets wounded. He’s still conscious and capable of shooting his gun, but he’s not able to advance to a position where he can finish the fight.

At this point, unless the bad guy just decides to give up, our good guys still have to do something about him. So what happens next? Ted and Ting are going to reverse roles. Our original Ted is going to hole up behind cover and lay down suppression on the bad guy, and our original Ting is going to become our new Ted and move in to finish the fight. New Ting lays down the hate, and new Ted dashes up to our bad guy to put an end to his assault at close range.

The Big Picture

Two is more than twice as good as one, but the two have to coordinate their efforts in order to take full advantage of their numbers. We want to have one person/unit serve as the Main Effort that will actually accomplish the mission, and the other act as a Supporting Effort that enables the Main Effort to succeed. That 90º angle depicted between Ted and Ting in the diagrams above is the ideal angle for best support between the two elements. We should always work toward this angle in order to catch our enemy in the horns of a Combined Arms Dilemma.

The fundamental tactical principle of the Supported/Supporting relationship can be applied whenever you have two elements. It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about an armed Citizen-Warrior couple dealing with a criminal assault, police officers making an arrest, or two military units securing an objective; the principle remains the same. So think about where you can apply this in your life. Wargame out scenarios and what you might do with your armed partner. And always remember: if the good guys are smart enough to figure out this tactic, then the bad guys are, too. Be aware that this is a tactical fundamental that spans all of human existence, and be prepared to deal with the situation from the losing end.

Great article!!! This was very informative, easy to understand and applicable to every Citizen-Warrior!